AI Context Behaviors

Before anything else, credit where credit is due: the basis of this blog post comes from this blog post by Andrew Fray as well as the GDC talk he gave, which was then expanded upon in this post by Mike Lewis.

Context Behaviors are an improvement to Steering Behaviors, an important staple of game AI that anyone who has dabbled in the subject is probably already aware of. This is explained in depth at the links above, but the basic idea of Context is that in real implementations, Steering either stops working properly or becomes an architecture mess, especially when things like collision avoidance are introduced. Each steering behavior then requires redundant code and calculations to make sure that it does not provide a recommended force that would crash straight into a wall. As Mike Lewis states in his post:

“Each steering force (…) needs redundant logic for obstacle/collision avoidance (…). As the number of forces increases and the complexity of logic scales up, it can be cumbersome to create clean code that is both efficient and does not needlessly repeat complex calculations. Generally, good implementations of steering become a layered, twisted maze of caches, shared state, and order-dependent calculations - all of which fly in the face of good engineering practices.”

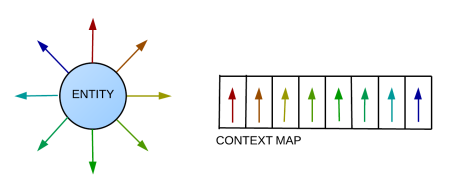

Context Behavior solves this by introducing the concept of a Context Map. A Context Map is basically an array (or a vector) where each index represents a different direction. For example, in a Context Map with a size of 4, each index would be a cardinal direction. As you increase the size of the array, the number of directions and the “resolution” of the map increases.

The Decision Maker class initializes two of these maps; one for Interest and one for Danger. A series of evaluators or contexts then run on these maps, one direction at a time. A “SeekTarget” context might, for instance, fill a direction with a greater value when objects get closer to the source or more aligned with that direction (through the use of the dot product). Finally, the Decision Maker will go through the Danger and Interest maps, and choose a direction to go in based on its given criteria for combining the two.

This form of AI-driven motion is useful for a wide variety of games. Anything that would benefit from classic Steering will benefit from Context. One of the best examples is racing or driving games, where the directions in the Context Map can correspond to racing lanes rather than cardinal directions, for instance; this is what Andrew Fray originally developed them for. However, any game with simple movement can use Context to get more complex and accurate behavior. It is not restricted to a particular platform or genre. With well-crafted evaluators, Context can perform simple pathfinding without the mess of code that would be required for Steering to do the same.

Now that the basics are covered (very briefly—I highly recommend reading the above links thoroughly to get a better understanding of the concepts), let’s look at my implementation.

C++ Implementation

This project is built on a framework developed over the course of the last semester in my AI for Games class, and the very base was given to us at the beginning of the semester by our professor Dean Lawson.

The first class I wrote when building this was the ContextDecisionMaker. This is the class that uses all of the individual Contexts to choose a direction. The first function I wrote was the update function for the ContextDecisionMaker, as it directed my design choices. Hopefully, the code mostly speaks for itself:

void ContextDecisionMaker::update()

{

//Get the data we need.

Unit* owner = gpGame->getUnitManager()->getUnit(mOwnerID);

PhysicsData data = owner->getPhysicsComponent()->getData();

Vector2 ownerPos = owner->getCurrentPosition();

//Create maps and initialize completely to zero.

context_map_t dangerMap(NUMBER_OF_DIRECTIONS, 0.0f);

context_map_t interestMap(NUMBER_OF_DIRECTIONS, 0.0f);

//Fill danger map.

fillDangerMap(dangerMap, ownerPos);

//Use the danger map to fill only the unblocked slots in the interest map.

fillInterestMap(dangerMap, interestMap, ownerPos);

//Get the best direction to go in.

Direction strongestInterest = chooseBestDirection(interestMap);

if (strongestInterest == Direction::NONE)

{

data.acc = data.vel * -5.0f; //slow down.

}

else

{

Direction leftDir = strongestInterest.getDirToLeft();

Direction rightDir = strongestInterest.getDirToRight();

//Blend the strongest direction and the two directions next to it.

Vector2 blendedDir =

DIRECTIONS[strongestInterest] +

DIRECTIONS[leftDir] * interestMap[leftDir] +

DIRECTIONS[rightDir] * interestMap[rightDir];

blendedDir.normalize();

//Accelerate in that direction, adjusting for our current velocity.

data.acc =

(blendedDir + (blendedDir - data.vel.normalized())) * data.maxAcc;

}

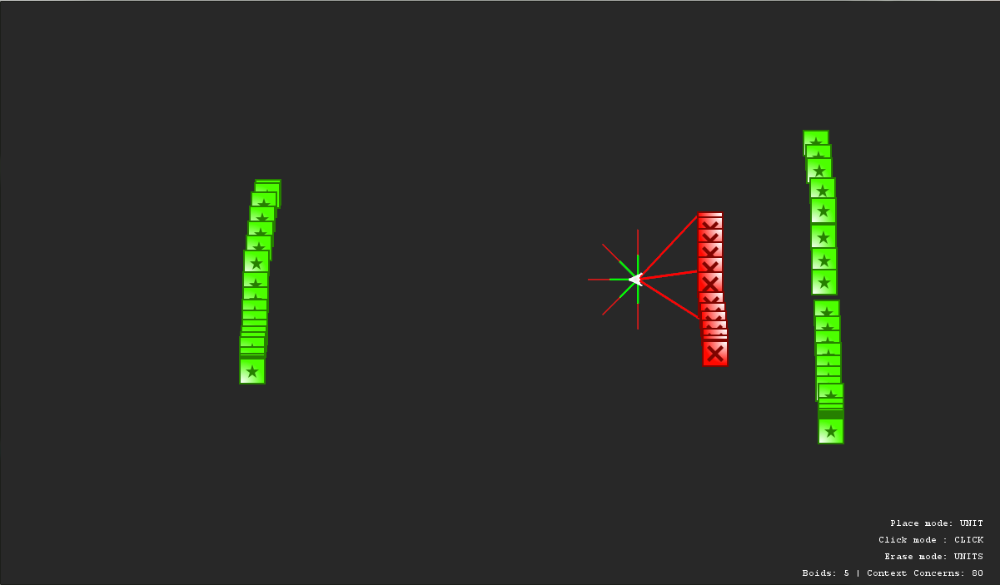

mData = data;

}Essentially, it fills the danger map first, then fills the interest map by ignoring directions in which there is danger above its “MAX_DANGER” value (which is data-driven through an XML file). It then loops through the Interest Map, picks the direction with the highest value, and accelerates roughly in that direction. One of the main points of Context Behavior is that this simple act of ignoring directions that have danger in them allows you to create complex and consistent behavior with very simple code. Here’s an example:

One of the important aspects of this is that the chosen direction is not directly where the unit goes. Instead, it takes its most desired direction and then blends that with the directions to either side, weighted by its interest in those directions. The result of that (plus using the dot product weighted by distance to determine interest) is that even if the agent is only considering a small number of directions, it can utilize diagonals and create more interesting behavior. In the next video, you can see a series of agents using a context resolution of only 4 head directly towards an interest through this blending:

This blending is an important aspect of Context Behavior. It means that, if your resolution is dynamic, you can change the complexity of your AI calculation on the fly based on the needs of the situation and the game, and still get good-looking behavior. A higher resolution generally gets smoother and more accurate movement, but at the cost of having to do more calculations. The complexity increases linearly as the number of directions considered increases. The following video demonstrates the effects different resolutions will have on the behavior, and the benefit of making it dynamic:

For this system, I built a dynamic constant loading system. It uses an XML file to manage the values, and sets up a watcher thread with Windows to look for file write notifications. When a write occurs, this thread sends a notification to the main game thread that it needs to update the values. Thus, all the player needs to do to try out new values is type them in and hit save, and they can watch their changes take effect in real time.

Compared to Steering, Context is much more customizable. Here, there are only two things that each agent considers: going towards the green interests and staying away from the red obstacles. However, it is trivial to add extra contexts, and the number of contexts only increases the complexity of the behavior linearly. Well-crafted “danger” contexts could, theoretically, speed up the overall algorithm’s running time by eliminating more directions that the “interest” contexts have to consider. The flexibility here, especially compared to Steering behaviors (which tend to collapse as you add more and more), is very notable.

Overall, I massively prefer Context Behavior to Steering. The code is significantly simpler for mostly better and at worst similar behavior. It is much more scalable and allows you to dynamically adjust the required processing time on the fly without totally sacrificing behavior fidelity. To my knowledge, while the blog posts linked above are very helpful and informative, there are no interactive demos of Context Behavior available online right now. With this in mind, I’ve decided to upload the executable project here so that you can try it out and see what you think:

Download the Context Behavior demo now!

This was one of those projects that I spent a lot of time playing with and trying out fun things while procrastinating on other work (like writing this blog post). As a bonus, here’s one of my favorite accidents I discovered while experimenting with how the agents would react to different situations: